The right choice for better business

For organisations to be drivers of a greener, more equitable world, decision-makers must rise to the challenge of ethical leadership.

Guided by strong ethics and smart strategy, decision-makers can transform their business’s impact to make the world better. Choosing ethical leadership pays off with increased consumer confidence, employee satisfaction and investor support. But it’s a path requiring smart navigation.

Professor Mette Morsing, Director of the Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment at the University of Oxford and Trinity’s 2024 Gourlay Visiting Professor of Ethics in Business, has been collecting corporate social responsibility (CSR) reports for more than two decades. In that time, she has led business schools, advised boards, and headed the United Nations Global Compact for Responsible Management.

Mette has noticed CSR reports evolve from optional, feel-good pieces with ‘a lot of aspirational talk’, to heavily scrutinised documents influencing every level of business operations.

Professor Mette Morsing

Professor Mette Morsing

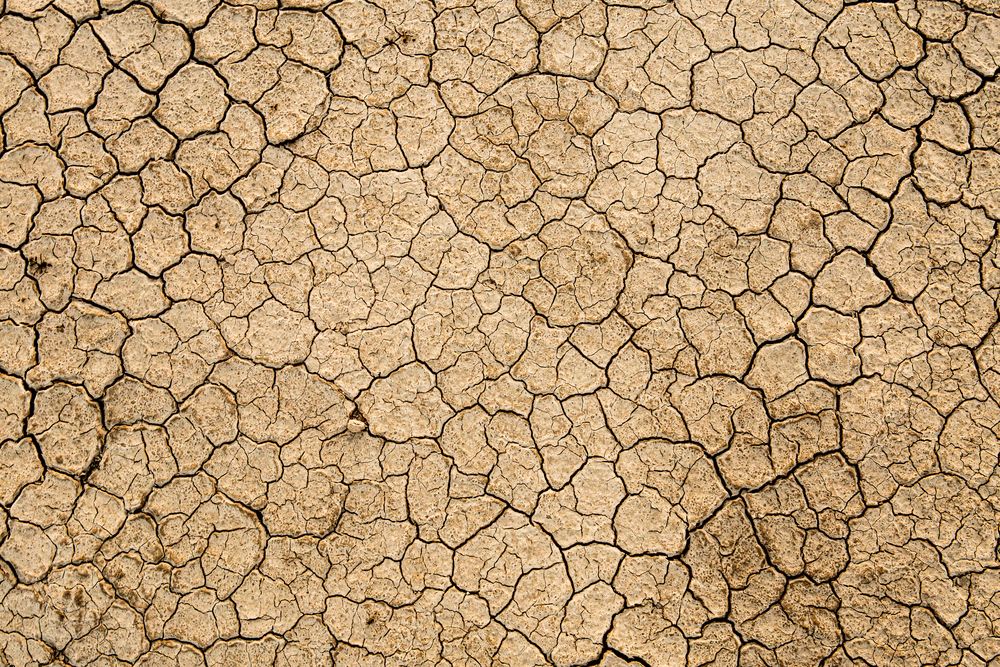

The change, Mette says, has been sparked by the planet in crisis. While there have always been business leaders feeling an ‘ethical responsibility to serve the world via their profession’, global crises like floods, melting polar ice and wildfires (not just in Australia; Mette saw smoke blanketing New York City from 2023’s Canadian fires nearly 1000 kilometres away) have spurred others to take action.

‘They witness this and get scared to an extent where they actually see their own powers and responsibility, and start to act,’ says Mette.

There’s an increasing awareness of human rights too. In 2013, the Rana Plaza in Bangladesh collapsed, taking the lives of more than 1000 garment factory workers producing textiles for multinational brands. The world’s attention turned towards poor working conditions, resulting in consumer boycotts. Competing companies united for a solution.

While crises can trigger awareness, Mette points out that consumer demand is rarely the main driver for organisational change.

‘Consumers are still oriented towards particular brands they like, or the price.’

Beyond an individual leader’s moral imperative, what then prompts an organisation's ethical evolution? The answer could be a looming spectre of business risk, sharpening both stakeholder focus and investor attention. And it may prove the most effective way for ethical leaders to get buy-in.

Being pro-green and anti-modern slavery, for example, can guard against the collapse of supply chains and keep businesses on the right side of newly introduced legislation.

‘Investors see regulations coming in the EU. They have seen the Inflation Reduction Act in the US [addressing climate change]. Investors think, if we are not at the forefront then we may impede our market opportunities in the long run,’ says Mette.

Mette’s team at the University of Oxford is analysing decades worth of marketing material and internal documents from the fossil fuel industry. Using AI, they’re comparing the industry’s repeated claims of decarbonisation to actual results. If they can show misleading conduct – creating a false impression in consumers – the industry may risk costly legal action… a result investors would be keen to avoid.

The first step for businesses of any size that are interested in making change is to conduct a materiality analysis. It’s a method of engaging stakeholders to discover which environmental, social and governance issues are most important for the organisation to uphold.

From there, leaders can make more effective decisions. ‘But,’ Mette warns, ‘to have a real impact, you have to look at the products and services you deliver, and your supply chain.’ This gets to the heart of each organisations’ unique power to make a difference. Using a financial company as an example, Mette points out that turning off the office lights each night, or printing double-sided, is ineffective compared to making strategic decisions to invest millions in eco-friendly Company A compared to gas-guzzling Company B.

The biggest misunderstanding business leaders have, according to Mette, is thinking they have time to address issues later.

‘They think that this is going to happen far into the future, rather than understanding it's actually now.’

READ NEXT STORY >>> MARKETING TO THE NEXT GENERATION

<<< BACK TO CONTENTS