Engagement in the modern-day church

Church attendance and the concept of faith in Australia is evolving, so what do church leaders need to do to keep up?

The number of Australians claiming affiliation with Christianity declined by 1.1 million people between 2016 and 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics. The sharpest decline was evidenced in adults aged 18 to 25 years, with Anglicanism experiencing the biggest drop among all religious denominations.

In line with these findings, both the National Church Life Survey (conducted by NCLS Research) and IBIS World have noted that church attendance in Australia is steadily declining.

So how do churches continue to engage, and what strategies need to be employed to boost and retain numbers?

Building community

First things first: community is key. ‘Jesus always did things at a community level – never individual,’ says the Revd Heidin Kunoo (TCTS 2017), who is Assistant Priest at St Paul’s Anglican Church, East Kew, and Assistant Chaplain for Mission to Seafarers.

‘I’ve heard a lot of people saying that God is everywhere, so we can pray at home, we can pray by ourselves, we don't need to go to church. And I agree with the first part; yes, God is everywhere …

‘However, we are also called to pray together as a community and worship God. Praying at home is to nurture yourself, but praying with the community is to deepen your faith.’

The Revd Heidin Kunoo (TCTS 2017)

The Revd Heidin Kunoo (TCTS 2017)

As well as coming together in worship, Heidin, who studied a Bachelor of Theology at Trinity College Theological School, believes engaging with the wider community on a social level is important. For St Paul’s, this means organising a parish lunch once a month at a local pub, plus a weekly morning tea, which attracts not just parishioners, but community members who don’t want to attend church per se, but still want to connect with their church community.

The Revd Professor Mark Lindsay, TCTS Deputy Dean, Academic Dean and Joan F W Munro Lecturer in Historical Theology, agrees. At Christ Church Brunswick, where Mark serves as an associate priest, community engagement is part of the church’s core business.

The Revd Professor Mark Lindsay

The Revd Professor Mark Lindsay

The church runs a social enterprise café on Sydney Road, and its previous vicar, Bishop Lindsay Irwin, played a crucial role in connecting the church to the wider community by working as a barista. ‘He was always there behind the counter in his collar serving people and striking up conversation,’ says Mark. ‘It was a really great way for the community to get to know him.’

Taking the church’s community engagement a step further – the clergy, including Mark – made a conscious decision to wear their cassocks and collars when out and about in Brunswick. While some priests have at times found that challenging, especially in the aftermath of such events as the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, the team has drawn inspiration from Bishop Lindsay’s example, and ‘personality and charisma’.

‘All of us on the clergy team are quite comfortable walking up and down Sydney Road, going into the shops and going into the Cornish Arms hotel wearing our cassocks when we sit down to have a beer,’ Mark says. ‘It probably looks a bit anachronistic and weird, but it’s become a natural part of how we inhabit that ministry.

‘Sometimes, it’s why people start to come into the church. They get drawn in out of curiosity, wondering what are those guys doing dressed up in black? It creates opportunities for conversation and for people to come in and have a look around and see what's going on.’

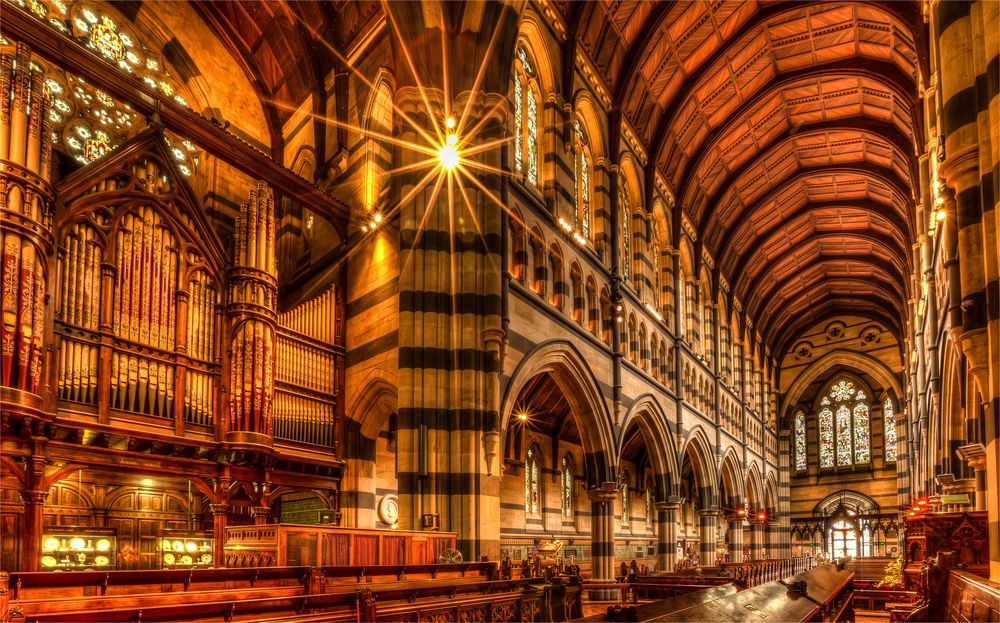

St Paul’s Cathedral in the Melbourne CBD has the benefit of being one of the most beautiful spiritual places in Australia, so naturally attracts worshippers and passers-by. However, its success in a strategic sense – particularly when it comes to funding – hasn’t always been a given, and is something that the Very Revd Dr Andreas Loewe, former senior chaplain and senior lecturer in theology at Trinity College, has worked hard to address since being appointed in 2012 Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral and Dean of Melbourne.

The Very Revd Dr Andreas Loewe

The Very Revd Dr Andreas Loewe

‘Over the last 12 years, we have really set up the cathedral for growth and particularly set it up in a way that is financially sustainable,’ says Andreas.

‘Previously, we were always short of funds or facing deficits or short on staff or volunteers, and we very strategically invested in growing the number of our volunteers and growing the number of our staff, both administratively and pastorally, so that the cathedral can run in the way it was intended to, which is really like an English cathedral.

‘We are one of the few cathedrals in the southern hemisphere to retain a pattern of a daily coral evening service during term time.’

Regularity and consistency

Both Andreas and Mark believe that a calendar of regular and frequent services, and the sense that a church is always open, is key to a thriving church community.

St Paul’s Cathedral, open every day of the year, offers 16 weekly services and has been intentional in ensuring its services welcome a diverse range of people. In 2024, three new congregations were established, including one that is Farsi speaking, one that is Mandarin speaking (re-established post-COVID-19), and one called ‘Gather’, targeted at students.

‘In addition to our very internationally minded English-speaking congregations, where we’ve got people from more than 25 nations, we've got these three very specific congregations that also look to reach out to particular constituents within the CBD,’ says Andreas.

Christ Church Brunswick, which offers morning and evening prayer and a mass every day except Mondays, plus two Sunday morning services and a more informal ‘Bible and Beer’ gathering on Sunday evenings, is also open every day, from first light to sundown, and it’s subsequently become known as a safe space to pray or simply sit in silence.

‘I think the most obvious thing would simply be remembering what any church is meant to be there for in the community,’ says Mark. ‘It’s meant to be a visible, welcoming space where people can come and participate and, yes, encounter God. And they cannot do that if the church is either literally or metaphorically shut up as though it's somewhere that just exists for the people who are already inside it.’

Attracting the next generation

Creating a warm and hospitable space also means welcoming people of all ages, particularly young people.

‘We have babies through to 90-year-olds and everyone in between, and we’ve got a Sunday school program that we’ve had to divide into two for the numbers,’ says Mark, of Christ Church Brunswick, adding that the older kids sometimes also meet in the parish house on Friday afternoons.

As well as seeking a place to spend time with like-minded peers, Heidin believes young people are often attracted to a different kind of church service.

‘[Younger generations] are more motivated by instruments like the guitar and drums and modern music, rather than the hymns, piano or organ,’ she says, adding that the style of preaching is important too, having observed that younger people are interested in testimony that can be related to what’s going on for them in their life right now rather than learning about the theology behind the scriptures.

She also feels that board games or sports can help younger people bond in a religious setting, along with discussions that draw on the contributions of a wider group, as opposed to just one person standing at the front of a church.

For Andreas, ensuring that young people – including those with small children – feel welcome at the cathedral has been very deliberate.

‘If we want to have more young people, then we also need to accept the consequence of our worship being disrupted … It took a good three or four years for most people to come on board with that idea, but once we'd gone through that process, we confirmed that, yes, we do want to have a place where kids can run around and they're not going to be constrained or limited to a particular space.’

Embracing change, thinking strategically

Creating a warm and hospitable space also ‘Inevitably, [the way people engage with the church] will change,’ says Mark. ‘A lot of people in the churches get terrified by the census statistics – you see the plummeting numbers.

‘That's one way to look at it. The other way to look at it is that we are now, as a Christian faith, no longer able to hide behind that self-serving idea that Australia is a Christian country. We probably haven't been for a century, which is good because it reminds us that we have no guaranteed or self-evident voice in the public square.

‘We can't presume that the policymakers should listen to us before they listen to anyone else as we are just one voice amongst many. Because we can no longer make that presumption, it means we have to think much more seriously about what those key things are we really want to invest in, in terms of our energies and how we present ourselves publicly.’

For St Paul’s Cathedral, that investment includes championing social issues, and being a strong voice of support in the community. This includes refugee advocacy, First Nations recognition and reconciliation, tackling climate change, and advocating for a safe church, including for children and those experiencing intimate partner violence.

Ultimately, Andreas says it’s about thinking tactically about what the church represents and what it aims to achieve, and considering who it’s serving, and who it wants to serve.

‘You have to be strategic … we see ourselves very much like a not-for-profit, but I think some of the qualities that come out of the corporate world [apply], which is an emphasis on good governance and setting strategic goals, so that you can either meet them or you can work out why you're not, and therefore begin improving on meeting them,’ he says.

‘That's really important because if you don't have a plan, if you don't have a map, you don’t know where you're going.’

READ NEXT STORY >>> ETHICS: THE RIGHT CHOICE FOR BETTER BUSINESS

<<< BACK TO CONTENTS