In memory of Her Majesty

Queen Elizabeth II, 1952-2022

Once more the Royalist Society has triumphed in the midst of a society that is assaulted by rapid republicans to assert that Australia is still a country ruled by a Queen.

The College's third Warden Ron 'Bull' Cowan had ascended his own throne, being installed as Warden six years prior, when a young British princess became queen of Britain and the then Commonwealth countries, including Australia, in 1952. After 70 years - Britain's longest reigning monarch - 'Lizzie', as she was affectionately known around the world - died on 8 September, aged 96.

It shouldn't have been this way. Destined for a relatively quiet life, the niece of King Edward VIII, she was unexpectedly thrust in to the line of succession when her uncle abdicated in 1936. Her father, Albert, assumed the throne as George VI. Upon his death, the then 25-year-old princess would succeed her father.

It was a time of shifting sands. Though already well underway before the outbreak of war in 1939, the British Empire was a rapidly diminishing power. Perceived as traditional, even outdated, the 'younger', bold and rapidly rising global power was the United States. In Australia, a generational change saw established ties with the Mother Land weaken, as the Americanisation of Australian society grew during the 1950s and '60s.

This was the era of Westerns being beamed into Australian lounge rooms, the space race, the Cold War and – by the mid 1960s – Australia's commitment to follow 'LBJ' into the mire that was the Vietnam War.

Still, there were those that looked to Britain and the monarchy as a fundamental aspect of Australia's colonial heritage. It was a regular feature of college dinners in the 1950s, both at Trinity and at the neighbouring women's hostel Janet Clarke Hall, for the toast to be proposed to 'The Queen and College.'

Following Elizabeth's coronation, and particularly after her inaugural antipodean visit to Australia in 1954, the student body relished the 'appearance' of various members of the Royal family attending college activities, especially the annual steeple chase, Juttoddie. These would range across the full spectrum of both loyalist sympathies to sneer at the aged traditions of the monarchy.

'Her very high Royal Highness fell out of the Royal Carriage and felt her way to the dais', the Fleur de Lys magazine recounted in 1959:

Thus did the "fairy-tale" Princess, her eyes of bright royal blue and pink in the finest Windsor tradition, her dainty hand uplifted in condescending acknowledgement of her subject colonials, experience Trinity for the first, and almost certainly the last time.

The Royals attending Juttoddie in 1954, as part of their tour of Australia that year.

The Royals attending Juttoddie in 1954, as part of their tour of Australia that year.

The fervour that surrounded the royal wedding between Prince Charles and Princess Diana in 1981 encouraged a different tenor, clearly evident within the collegiate community.

A new college society emerged in the Trinity College Royalist Society (TCRS),

... a highly controversial dinner held by a highly controversial society, both of which, of course, never existed.

Relatively obscure for the first couple of years of their existence, the TCRS burst forward on the pages of the Fleur de Lys magazine in 1983.

Even since it had become public knowledge that the newly-wed royals would be undertaking a four-week tour of Australia, including opening Bourke Street Mall in Melbourne that year, 'the Royalist fraternity of Trinity College began planning their debut before the royal couple.'

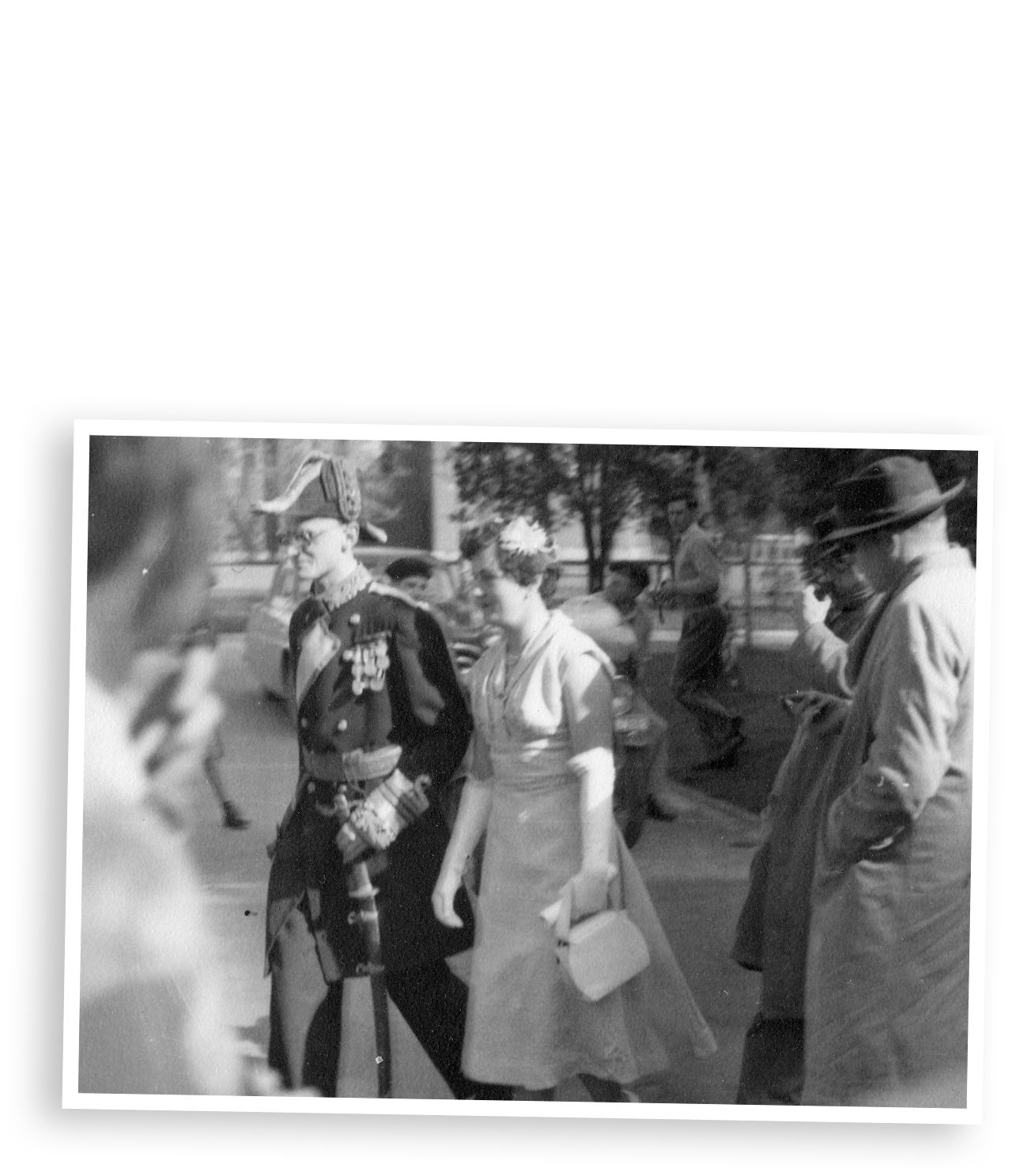

Dinner suits were picked out and flowers, suitable selections from the English Hymnal and deck chairs all had to be perfectly considered for the group of monarchists who ensured their place at the front of the barricade by arriving at the mall at 5am.

Members of the group later acknowledged they realised they may have been slightly over-zealous when they arrived to find themselves the only well-wishers and a bemused group of security preparing for the day's coming event.

But meet her they did. Dressed in black-tie attire at the front of the crowd of some 200,000, they had a plan should Diana make her 'pass' down the other side of the mall. As society president Andrew Messenger (TC 1980) recounts, the group were intending to sing her favourite hymn, I Vow to Thee My Country. 'We had done our homework', he remembers, 'We had that little nugget up our sleeves.'

Messenger was captured by photographer John Lamb greeting Her Royal Highness in an image that was splashed across the country's newspapers in the following days, and indeed around the world, in London in The Times and The Telegraph.

Messenger broke the news of his new-found fame to his parents back in Benalla from, appropriately, the Windsor Hotel. 'There was this resigned sort of sigh down the end of the telephone line and they said 'We know - we've been watching you all afternoon', with this hint of disapproval.'

But he was not put off by his parents contrary stance.

'For those who did participate in greeting the Princess of Wales, and even more importantly for those present who believe in a Constitutional Monarchy, the whole morning was a totally unforgettable and exhilarating experience.'

Messenger would later write that the 'aftermath was equally memorable.'

'I felt the deep personal satisfaction of one who had unashamedly achieved a long-term ambition in expressing his devotion and loyalty to both an essential and worthwhile institution and the people who so ably fulfil its offices.'

Now almost three decades later, Andrew Messenger is a lawyer who until recently spent his time back and forth between his home-base of Sydney, and Melbourne. He's now based in Madrid, Spain. However, a wry smile breaks his face whenever he happens to be in the city of his college years and finds himself at Bourke Street Mall.

'I do remember the controversy,' he admits, recalling the mall's design, but where else 'do you go and become intimately acquainted with a princess?'

The Trinity College Royalist Society continued throughout the 1980s and into the early 1990s, as the debate around Australia moving towards a republic gained momentum and support.

Trinity College can be assured that as long as loyal hearts still beat within its ivy towers, the world will be a better place and the grey dull clouds of petty republicanism will not triumph over the loyal forces that love all that is beauty, love and good things. God Save the Queen.

By 1993 however, pundits were observing that, 'like the Queen of Australia, the Trinity College Royalist Society faces a controversial future.'

At a Trinity College Associated Clubs (TCAC) general meeting that year, 'a small number of students' voiced their objections to the society's very existence, and the notion that it should receive any funding from the TCAC coffers to support the society's social events. 'The traditions of this society were maintained in an increasingly hostile and critical environment', society convenor and Senior Student Rob Heath (TC 1990) recalled.

As he noted, 'The society plays an important role in promoting rational discussion of the whole republican issue. Members have attempted to prevent the monarchy from being condemned and deplored without understanding. The Queen is our Head of State, and, although this is not the place to launch into a discussion of social cohesion and the decline of widely shared values, the institution deserves the respect of all, including those who seek to challenge and replace it. Change is probably inevitable, and this society is bound to play an important role in future debate.'

That change would have expected, but not entirely anticipated consequences 30 years on. Speaking with Rob the day after Her Majesty's passing overnight, he reflected on a small but significant change. These days a barrister on the Victorian Bar, he had gone to bed a Queen's Counsel and woke to find himself a King's Counsel. It would be the first time in more than 70 years, since George VI's death in February 1952, that the Commonwealth's legal structure had used the postnominal.

The issue of Australia becoming a republic continued to bubble throughout the student community during the 1990s. In 1997, two years before the nation would ultimately take the issue to a referendum, the Dialectic Society held a spoof debate on the issue of Australia remaining a constitutional monarchy.

'Spoof', because students would assume the roles of Australian singer Debra Byrne, the long-deceased Australian politician Sir George Wigram Allen, and controversial then-head of the RSL, Bruce Ruxton - who declared on the night, 'we don't have a president, never should have a president and never will have a president in this country if I have got anything to do with it.'

Debate expectations, when Australia took the subject to a referendum in November 1999, the 'republic' camp failed to secure the votes. Some 55% of the country voted 'no' to the two questions posed, although subsequent critics and observers have mused that the framing of the particular questions may well have played a role in the outcome, more so than the country's resistance to detach itself from the monarchy.

The referendum seemingly laid to rest both the issue of Australia moving towards a republic, at least any time soon; but equally may have been the final curtain call for the Trinity College Royalist Society. With the cause of debate having been extinguished, the group seemingly disappears from student publications as other global issues arose in the early 2000s.

Two decades later, the issue of a republic continues to quietly bubble along, like an undercurrent to the ever-changing plethora of Australian prime ministers; as Queen Elizabeth quietly continued in her role, with a serene steadfastness.

And now she is gone. And we have a king, in King Charles III.

To a monarch that saw out more changes and challenges in the way the world functions than any before her, and did so with grace and poise, it is perhaps fitting as a college built upon Anglican values to remember her in farewell with the adaptation to the oft-remembered prayer,

Eternal rest grant unto her, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon her. May she rest in peace.

Dr Ben Thomas, Rusden Curator, Cultural Collections

Dr Ben Thomas, Rusden Curator, Cultural Collections