Reginald Stock

Recollections, 1933

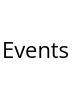

Reginald Stock (TC 1930) in this third year at Trinity College, 1933

Reginald Stock (TC 1930) in this third year at Trinity College, 1933

'Official College histories ... always need supplementation by anecdote and reminiscence. We are grateful to Trinity members who let us have stories from the past to show how events appeared to those who took part in them.'

Reginald Stock entered Trinity in 1930, studying first year Arts. He was awarded a Council Scholarship the following year and in 1933 was elected Senior Student. That year, Warden John 'Jock' Behan closed the College Buttery after a student incident, which provoked uproar. Stock, as Senior Student, was in the thick of the deliberations. Almost 50 years later, he recorded the circumstances of that year from the student perspective.

For Trinity College, the year 1933 was the year in which many longstanding problems reached crisis point.

As one of the participants in the events of the year, I have often wondered whether I should set down some of the things I remember about it. There was much to be said for leaving it all alone. Many of the people concerned had died or otherwise left the scene. It might be better not to re-open old issues, or even revive old bitterness.

Against this there was the desirability of keeping the record straight; there were occasional references in such things as College publications; and from time to time people interested in the College referred to the events or even asked me what happened.

I suppose there is a further argument that any history, great or small, may be some guide as to what to do and what not to do in the future.

I entered College as a freshman in 1930. Because of family considerations it was well into second term before I went into residence. The College then numbered under 100. Apart from the problem of getting to know my contemporaries and learning about the traditions and customs of the College – with its stress on seniority and the fact that freshmen were less than the dust – the organisation with most immediate importance for me was the Fleur-de-Lys Club, with its president and four committee members and its system of curators (usually second-year men) responsible for particular activities such as the Common Room and the Buttery. The senior members of the club then seemed to me to be men of ability and strong character, and I still think they were.

Like the other freshmen I absorbed what seemed to be the current opinion of the Warden, Dr J.C.V. Behan – "Jock". He was regarded as the authority in the College system, but as someone rather remote. As an individual he was to be avoided as much as possible, and was looked on with feelings varying from tolerance to dislike.

With his emphasis on forms and legal technicalities, many thought he was not to be trusted. Several years later, at a Fleur-de-Lys dinner, my predecessor as president in a speech referring to the early history of the College, said that the first title for the head of the College was "Principal", but then we had "Wardens" and since then we have had no principles.

It was a bon mot for the evening, but it did represent what a lot of ordinary members of the College felt.

Apart from seeing him in the distance in Hall on most nights, first and second-year men like myself saw little of the Warden except on formal occasions. One such occasion would be when, for some special reason, the Warden wished to address the members of the College. In that event, the club would call a formal meeting and the president would present the Warden to the members.

Of the staff, the Sub-Warden, Gordon Taylor, had more contact with members of the College than anyone else. He was responsible for dealing with minor breaches of discipline. Such personal contacts as he had with individuals were reasonably good.

The Chaplain, 'Thos' Robinson, was known through his conduct of Chapel services and his acquaintance with a few individuals. None of the other tutors was significant in College life. College tutorials either did not exist or were practically useless. Exceptions to this were, I believe the medical tutorials conducted by several doctors, none of them a resident.

The supper was a standard custom. At about 10pm after a few hours work three or four or half a dozen people would congregate in the study of some host, who would usually provide cocoa.

Discussion and argument would range over all things serious or trivial. I do not recall members of the staff ever being present, except that I believe on a couple of occasions the Sub-Warden was the host, and I remember Thos being the host or the guest on a few occasions.

At one stage the Warden himself asked a few people to supper, but on the one occasion I recall the atmosphere was far from relaxed. The Warden also occasionally had small dinner or luncheon parties, but these events were very stiff and the general feeling was that they should be avoided if possible.

It was not until the end of my second year that I began to realise that there was something more to the Warden than the standard view recognised. It was the requirement that one should pay a formal call on the Warden before going out of residence at the end of third term.

For some reason, I had to wait in an ante-room before going into the Warden's study; and I stood looking at what I recall to be some prints of Italian Renaissance paintings.

Suddenly the Warden's voice alongside me asked me if I was interested.

We had a few minutes' discussion on a subject of which his knowledge was much greater than mine. It was the first and almost the only time in which I can remember a relaxed discussion with him on something of common interest.

As time went on, I began to understand that under the stiff exterior was a very shy and highly nervous man who, while possessing in many respects a strong sense of purpose, nevertheless was basically unsure of his capacity to achieve his objectives.

All this he sought to conceal behind the stiff manner, the unbending posture, the insistence on formality, the ponderous speech both in public and in conversation. If he had a sense of humour, it was not allowed to surface: I cannot remember seeing him smile.

Personal relations were particularly difficult for him. It used to be said – probably correctly – that he had had a particularly hard time in the first few years after his appointment when, as a relatively young academic back from Oxford, he had to head a College with a large element of ex-servicemen from the First World War.

It was said that his experiences then confirmed his natural stiff reserve.

One result of all this was an inclination on his part to rely upon the letter rather than the spirit of the law. He was adept in legal technicalities and found it safer to make strict use of them rather than to adopt a more flexible attitude.

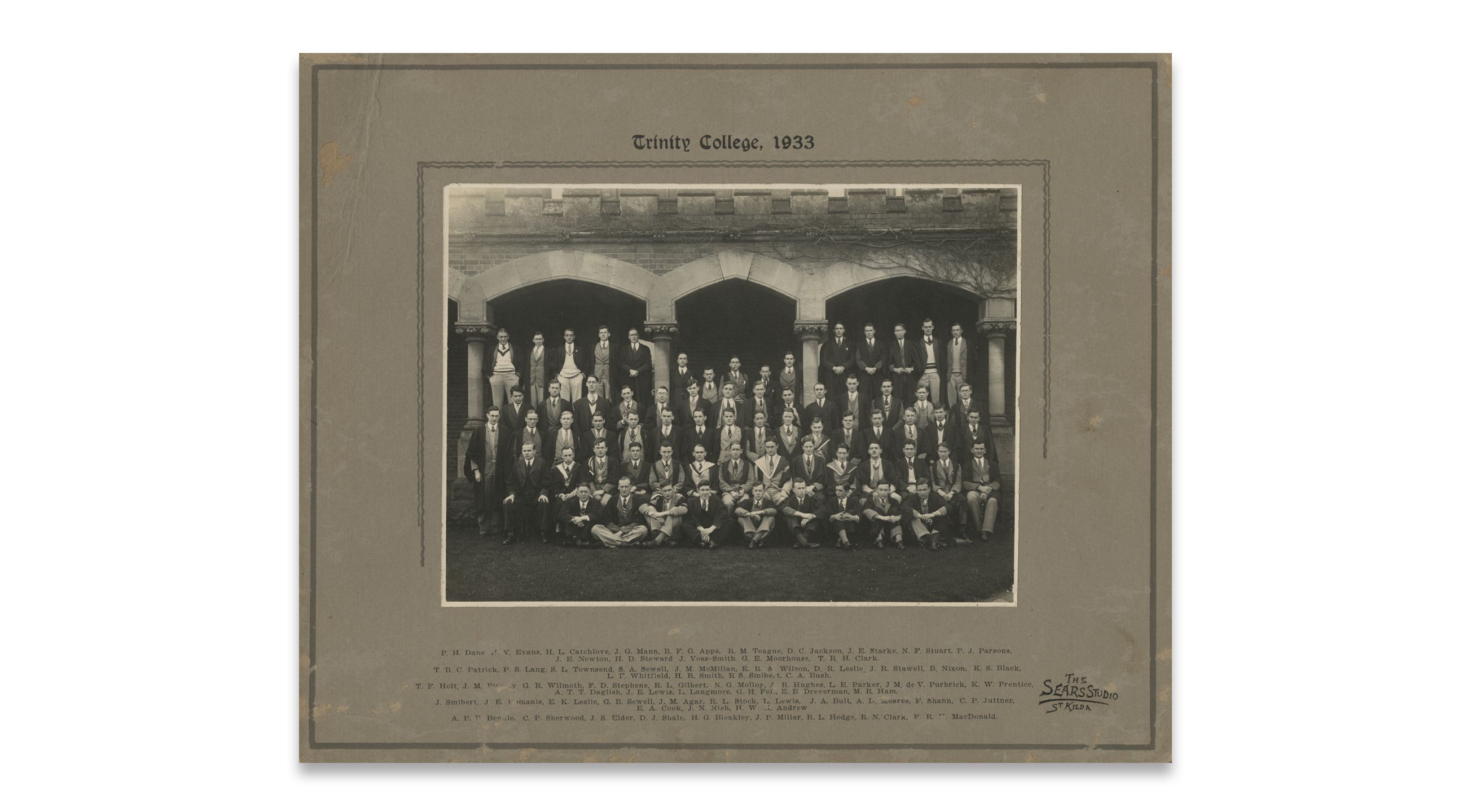

John 'Jock' Behan (TC 1903), Second Warden, 1918-1946

John 'Jock' Behan (TC 1903), Second Warden, 1918-1946

Another consequence was that he found it very difficult to discipline individuals who committed offences, major or minor, against the rules and customs of the College.

A frequent reaction was for him to threaten a reduction of privileges or some other disciplinary action for the College as a whole – a course which tended to provoke resentment amongst the other members of the College who were in no way involved. The Sub-Warden was much more effective in these matters in that when he thought fit to take some action he was quite capable of administering a stern rebuke or even a penalty to the individual offender.

None of this is to say that the members of the College were an assembly of angels.

They were the usual collection of mostly high-spirited young men, some of above average intelligence and some with special talents; some had well-to-do parents and were used to a measure of independence.

Furthermore, there was not the same pressure to complete a university course, as there was in the more crowded universities of the post-war years.

On the whole, people were fairly well behaved according to the standards of the time, but misbehaviour did occur and disciplinary action was called for from time to time.

Nor is it suggested that during those years life in Trinity was hell on earth. People went through their university courses and obtained their degrees; in sport, College teams played with the usual success or lack of it; there was the Trinity Ball and the College play; Juttoddie was founded; and there were the usual patterns of human relations with friendships formed, likes and dislikes developed, and sometimes arguments and high feelings generated over issues not connected with College authority.

I for one did not and do not regret the time I spent at Trinity.

Yet the fact remains that in the early '30s tension did seem to grow. One sign of this was that many people did not stay in College 'til the end of their university courses, preferring to spend the last year or two outside.

It may be that my generation was, to some degree, responsible for the growing tension. We were probably less badly behaved as individuals than earlier generations, but perhaps we took ourselves too seriously or, indeed, were too self-important.

Minor incidents seemed to increase, most of them on matters which I do not now recall. Some, but by no means all of these, related to drinking. Unlike all the other colleges, Trinity did have the Buttery, managed by two club curators. From there, beer could be obtained to be consumed in Hall. Apart from this, alcohol in College was strictly forbidden and so far as I know this rule was strictly observed.

Nonetheless there were well-known hotels in the vicinity, and through these and in other ways, occasionally some individual failed to observe the old tradition of drinking like gentlemen.

The Warden took a very strict view of any such offence which came to his notice, but his usual course was to take some action against the club as a whole.

In second term 1933, one individual was regarded as having overstepped the limits, but the Warden took no action until an outside body which claimed to have suffered from the individual's conduct brought such pressure on the Warden that he was obliged to ask the man concerned to leave the College.

At this time the club committee and most other senior members were in favour of fairly strict discipline in College. They were critical or, indeed, resentful of what they thought was the Warden's weak method of enforcing it.

On the other hand, it is fair to say that because of the failure of communication between the Warden and the members of the College, he was probably not aware of this attitude.

I do not recall as to whether it was right at the end of second term or at the beginning of the third, but without further warning the Warden announced to the club that because of the conduct of members of the College, the privilege of the Buttery would be withdrawn.

Apparently he thought that as the club failed to discipline its members it should lose the privilege, although there was nothing to suggest that any excessive drinking was going on in Hall. Any individual excesses were with liquor bought and consumed outside the College.

This move brought the tension and dissatisfaction to a head. There was animated discussion and argument as to what should be done, and the opinion rapidly grew that, as all other methods of improving relations with the Warden had failed, then – as someone put it – 'We had better try some dynamite'.

At a general meeting of the club a resolution was passed, that 'This club take steps to procure the removal of the Warden'. There was only one vote against it, and that was from someone who, I think, did not disagree with the general dissatisfaction but doubted the desirability of the proposed action.

The committee was given the task of presenting a letter with the information as to the resolution to the Archbishop of Melbourne as President of the College Council.

Before doing this, however, the committee thought it proper to wait on the Warden and inform him of the resolution.

The Warden was obviously deeply shocked, but after some moments' pause said: 'Would you withdraw this resolution if I restore the Buttery?'

As spokesman, I replied that I did not think so since the Buttery was the occasion rather than the cause of the trouble. Later that day, the letter was presented to the Archbishop at Bishopscourt.

I do not know what discussions took place in the College Council, but clearly the situation was regarded as being serious. The immediate outcome was that a member of the Council, Professor Wadham (later Sir Samuel) was asked as a kind of committee of one to discuss the whole problem with the club committee. Over the following weeks long and intense discussions took place. The Council considered the matter further, and a committee of Sir Richard Stawell, Professor Wadham and, I think, Dr Mark Gardiner were asked to announce the Council's decisions to the club.

These were that the position of the Warden must be maintained and he would remain the final authority in the College.

However, a new position would be created, of Dean, and it would be the Dean who was responsible for handling relations between College authority and the members of the College. In particular, he would be responsible for discipline.

I well remember Sir Richard, with characteristic firmness combined with gentle charm, announcing all this to a meeting of the club in the Common Room. I think it fair to say that everyone in the club was delighted with this outcome and accepted the Council's proposals with enthusiasm.

It seemed that the club's objectives had been achieved.

Student sketch of the College Oak and Bishops' Building, 1931

Student sketch of the College Oak and Bishops' Building, 1931

An uneasy calm prevailed in the next few weeks. The Dean's appointment would not, of course, be effected before the New Year, and the Warden remained in immediate charge. There were a few of what seemed to be minor incidents.

I recall one rather immature freshman arriving back in College rather the worse for wear, and I understand meeting the Warden apparently patrolling one of the corridors in a way which hitherto had been quite unusual.

Rightly or wrongly, there was the impression that the Warden was looking for an opportunity to 'get back' for what he must have regarded as a bitter humiliation.

Towards the end of term there were one or two minor 'rags' and I recall, on one evening, several fire extinguishers were released by junior members with active discouragement from seniors.

I may add that apart from members of the College Council there were a number of other senior people in the University who were aware of the troubles in Trinity. I myself had confided in Professor Bailey (as he then was), Dean of the Faculty of Law, and John Foster, then acting-master of Queen's, both of whom were sympathetic, although I would in no way say they were responsible for the action that we took.

As exams for the university at the end of the year were beginning for most of us, the Warden required a meeting with the club. This was held in the Common Room. The Warden entered and read a brief statement to the effect that the Fleur-de-Lys Club was dissolved forthwith, but so far as I recall, no reason was given.

In the weeks that followed, exams were interspersed with meetings and discussions amongst ourselves, with senior friends and with legal advisers. The strict legal position seems to have been that while the Warden could probably outlaw the club from the College and in practice make it impossible for the club to operate, he probably had no power to dissolve what was an independent if unincorporated association with its own funds and other assets.

The College closed for the year with the issue still undecided.

During the long vacation each member of the committee received from the Warden a notice requesting him not to return to the College in the New Year.

Under the then constitution of the College, the Warden, under one rule, had power to expel any member of the College, but the member concerned had the right of appeal of the College Council.

Under another rule, the Warden had an additional power to require at the end of the College year that a member should not return in the following year. It was under the second rule that the Warden had acted.

One of the five had already stated at the College that he did not intend to return in 1934, and I believe sought and obtained a withdrawal of the notice.

The rest of us gave serious thought to the possibility of legal action on such grounds as the denial of natural justice. There were discussions with individual members of the Council. However, it was apparent that litigation might be unsuccessful and would certainly be most unpleasant.

It would be difficult for the Council to reverse the Warden's decision as to the club, which would have inflicted an even greater humiliation upon him.

As individuals, we had had enough of the tension of the previous year. All our friends had left College, and indeed I think we would have been the only fourth year men proceeding to fifth year. We thought the change in the College organisation which we had originally sought, had been achieved. We therefore indicated that, provided the assets of the old club could be handed over to the new club which would be set up, and not fall into the Warden's hands, we would take no further action.

I do not, at this stage, remember who the intermediaries were, but the arrangement was agreed upon. I think the only time I met the newly appointed Dean was when the transfer of property was being arranged.

I remember that the atmosphere was not particularly cordial.

My final year was spent out of College and I do not think it suffered from that; nor did I feel then, nor did I subsequently feel that I had in any way been discredited by what happened, amongst my contemporaries, or my elders. The troubles of Trinity were too well known. Yet it may be that some of us may have been too impulsive and perhaps too arrogant in our responses to the difficult circumstances which more mature people might have handled differently.

The real tragedy was that of the Warden himself. In spite of his many qualities, he was not suited to the job which he had to do, and he suffered deeply in the result.

I well remember an occasion in third term when Mrs Behan asked me to see her, and I spent an hour or more with her walking up and down the garden behind what was then the Warden's Lodge, while she complained to me about the unfairness of the attitude of myself and the College toward her husband, and spoke of the unhappiness this caused him and her, while I tried quite unsuccessfully to explain our point of view.

Probably in the long run all turned out well. The system of the Dean seems to have worked well.

College life resumed with something like normality and it was probably for the best that the old guard of the Fleur-de-Lys Club were no longer there.

The Warden went on to achieve much for the College, legally and financially. The old jibe of my day that the gifts which the Warden gained for the club did not come from people who had been through the College was no longer true if it ever had been. Those of us involved in the trouble did not suffer in our later careers, and may indeed have learned something from the experience.

I believe we lost nothing in our interest and affection for the College.

Remembrances of Reginald Stock (TC 1930), provided back to Trinity College in 1984.

Dr Ben Thomas, Rusden Curator, Cultural Collections

Dr Ben Thomas, Rusden Curator, Cultural Collections