Walter St. George Sproule

Recollections, 1896-1900

'My first year was 1896. I was just 17, which will account for the impact some of the personalities and happenings made on my mind. '

Trinity at that date had more or less recovered from her very serious set back caused by the "Ninety row" though her numbers were still low. Most of the older and senior men were theologs, of whom there were some 13 out of about 40 residents all told. The College was not full. There was no Dean: there was one resident tutor - Mr E. G. Hogg, later to become Professor of Mathematics or Physics in the University of Tasmania. For logic and law subjects, Mr J. T. Collins, an old graduate of the College, and Principal of Trinity College Hostel (not yet named Janet Clarke Hall) acted. Classical subjects, of course, were the province of the Warden, Dr Leeper, who was at his best in these lectures. Many of the Ormond students used to attend.

The College was without a chaplain of its own until about 1898. The Senior Student was, to my young mind, a most impressive person - T.T. Slaney Poole, M.A., back to Trinity to finish his law course after a year's absence as Acting Professor of Classics at another university. He later became a very distinguished Judge of the Supreme Court of South Australia.

I shall speak first of what after a lapse of 65 years, has come to mean to me more than the memory of happenings — the outstanding personalities of Trinity during my time. And first I must place one who came in as a freshman in 1896.

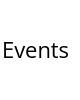

A good deal older than the others of us in the first year was a theolog George Merrick Long known almost from the start as Cassius, after Cassius Longinus, a name familiar to all of us, and because, being tall and rather gaunt, he was held to have "a lean and hungry look." And to us, his friends, he always remained "Cassius" even when a Bishop.

Long, without trying, exercised a great influence in the College, entering fully into its life, and from the first captured the confidence of Dr Leeper, and so was able to be of great value, for the Warden was not an easy man for a student to deal with.

I remember well his coming to Trinity College, a tall, well-built youth with a moustache. His character, his social gifts, that magnetic personality, which was even then in evidence, made him a general favourite.

In May, 1896, Browning's "Strafford" was performed by the students of Trinity in the St Kilda Town Hall. I smile now at the irony of the fact that while I was allotted the task of John Pym, G.M. Long was bracketed with several others as mere Presbyterians!

George Merrick Long (TC 1894), educationalist, and later Bishop of Bathurst (1911-1928), then Bishop of Newcastle (1928-1930). Vandyke, c. 1910s. National Portrait Gallery, London.

George Merrick Long (TC 1894), educationalist, and later Bishop of Bathurst (1911-1928), then Bishop of Newcastle (1928-1930). Vandyke, c. 1910s. National Portrait Gallery, London.

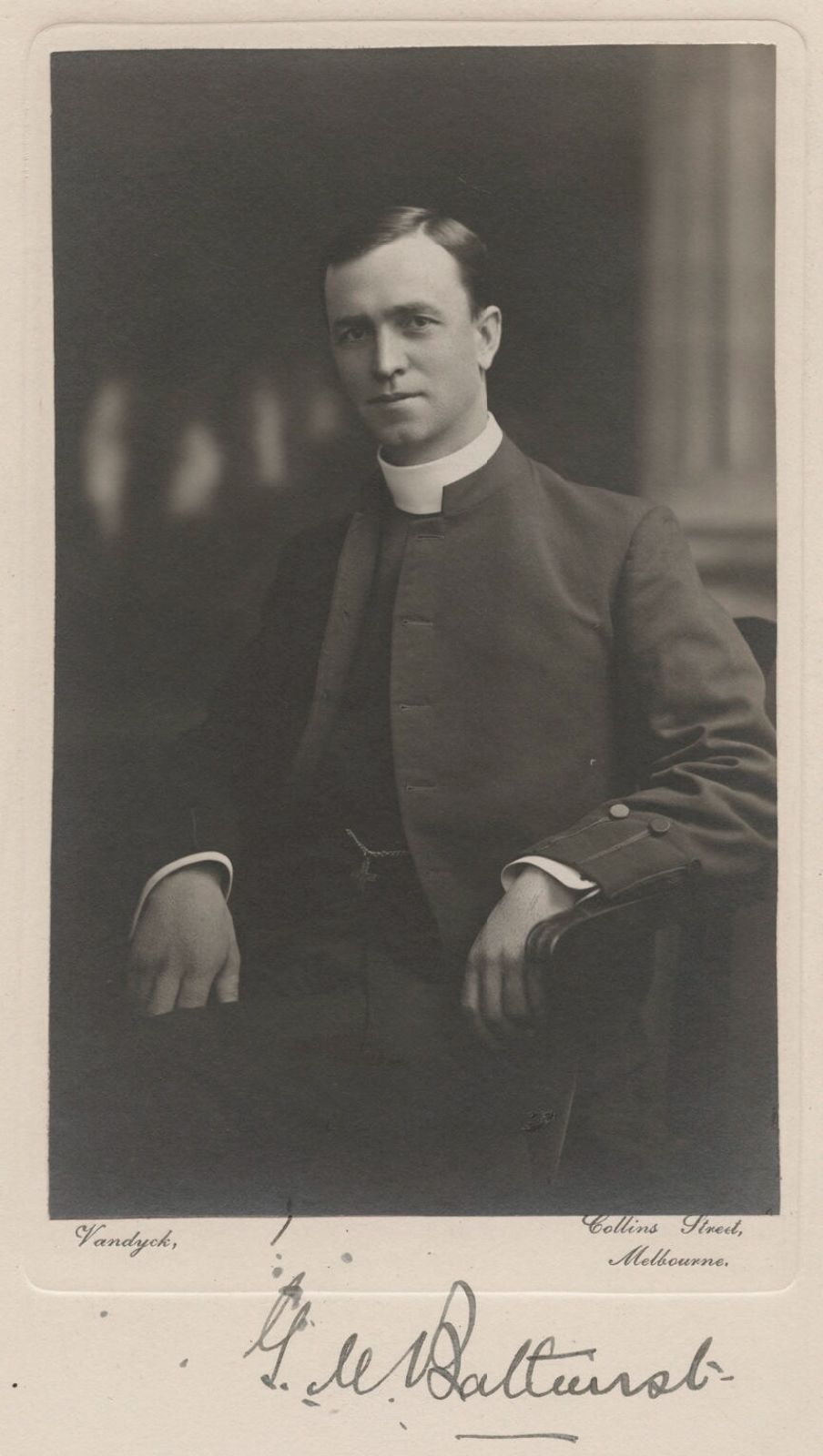

Another outstanding figure, Hugh Bullivant - dead only lately in his eighties - was such a man as might have been in the mind of Cecil Rhodes when founding the Rhodes scholarships. Bullivant, coming up from Melbourne Grammar, was a natural leader.

Competent, though not outstanding, in his scholarship, he went through his arts and law courses without ever failing, and in each of his five years represented Trinity against Ormond in cricket, rowing, football and tennis, as well as rowing several times in the intervarsity race. In some years he captained the cricket and football, and more than once stroked the crew.

Second Lieutentant Hugh E. Bullivant (TC 1893), c. 1918. Imperial War Museum, London.

Second Lieutentant Hugh E. Bullivant (TC 1893), c. 1918. Imperial War Museum, London.

Anyone who has represented the College in two or more events in the year, to say nothing of rowing in the varsity boat here and in other states, must realise that one who can manage his year too, must be out of the ordinary, even though he does not appear high up in the class lists.

Bullivant, a strong, forthright and likeable character, never practised law, but went on the land - his people were station folk - and within two years he was President of the Pastoralists' Association in his district.

Many years later he led the fight in the law courts in the attempt to establish the rights of landowners to fair compensation for land resumed by the New South Wales Government; and though he, to his great cost, failed, his action shamed the State into giving the dispossessed landowners a good deal more.

Geelong Grammar, like Melbourne Grammar, sent many to Trinity. Most remarkable among them, I think, was Charles Belcher, a very brilliant classical scholar and a considerable athlete, rowing in the College and varsity crews, and being in our running team.

He went into the British Colonial service, and after a very distinguished legal career, in the course of which he became Chief Justice of Nyasaland, Cyprus and Trinidad and Tobago in succession, retired some 20 years ago to Africa, where he laments the ungodly mess the English politician has made of what he knew as a loyal and peaceful part of the British Empire.

Wesley College provided us with our outstanding all-round athlete Harold John Stewart, later to become its headmaster. H.J., as he was called throughout his time in Trinity (to distinguish him from another Stewart, Percy Bysshe, often called Cherrybottom - (chemistry students can explain) - was a wonderful footballer. Half the senior teams sought him; one at least offering his their captaincy, but he was loyal to the Collegians. Also, H.J. was a first-class fast medium bowler and a glorious field. In running, too, he was our best sprinter. His influence was very strong in the College.

Walter Sproule, standing third from left, with fellow members of the Trinity rowing crew during his second year at college, in 1898.

Trinity College Archives, MM 002778

One who was in during the whole five years, doing arts and law, was A. A. Uthwatt, who at the end of his third year shared the final honors scholarship with a first-class in logic and philosophy, was Senior Student in his last year, and finished up in March top of the list in the law finals with the scholarship and the Supreme Court prize.

That year he went to Oxford, then to the English Bar, became a Chancery Judge, and later had the very rare distinction of being made a Lord of Appeal in Ordinary without having served in the Court of Appeal. He died while sitting on the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council during the hearing of the Bank Case.

Charles Gavan Duffy, who came in about 1898, was our star debater in the Dialectic Society - later he was to sit on the bench of the Supreme Court of Victoria. In sport we were handicapped by our small numbers as compared with Ormond - at first our only opponent. In cricket we held our own, only losing one match. In rowing we won a most unsatisfactory race on a foul in one year. But only once did we manage to win the football. Usually we got beaten badly - we would have half a dozen or so real stars, a reasonably decent middle section, and six or seven who would not have got into the under 15s in any public school. In tennis we were usually adequate, though Queen's beat us, thanks to their possessing the reigning Victorian singles and doubles champion, Gus Kearney. Trinity had an interstate cricketer in Tommy Drew - a five feet four inches little man - an outstanding batsman with an ability to hit the ball out of the ground and a reputation of being one of the two best lacrosse players in South Australia.

In 1896 the College had no amenities at all, save perhaps the billiard table.

There was no sewerage at any time during my five years in College - we relied on the "Pilgrims of the Night." Situated at the west end of the Clarke building, the lavatories were accessible only from the end of the cloister, and for some reason the door was locked at night, and not opened until after nine in the morning. As a result, in the mornings the route to them was through the window of the study next on the west of the locked door. I was the occupant of that study for my first two years, but as my fellow occupier was much my senior and accepted the position, I accepted it, too.

Needless to say I got to know my fellow students sooner and in greater number than I otherwise might have.

Work was the dominant note in the College, I now realise. We were not an affluent lot - few of us had much money and those who had never showed it - except one, who approached the committee which exacted the 2/6 fine for missing Chapel with an offer of "five Chapels for 10/." It was declined.

There was not much going out socially, compared with later years I knew of, and very little row in College at night. We had no initiation "rags" then, though a freshman was liable to be pulled from his bed in the middle of the night. We had to be in by midnight - the hotels used to close then at eleven. To stay out all night you had to apply in the leave book, stating where you proposed to spend the night.

Leave to stay at a hotel was never granted. So strict was this rule that when on one occasion one Russell Clarke, son of one of the principal benefactors of the College and a theological student at the time, applied for leave to spend the night at a particular hotel, he was sent for by the Warden, who said it was not possible. On being told by Clarke that his father had taken all the accommodation in the hotel for the purposes of a Hunt Club, and would be residing there himself, the Warden said: "That makes a difference. Just put 'At the residence of Sir W. Clarke' and it will be all right." Clarke indignantly refused, and spent the night in College.

A good idea was the seating at tables in hall. Each table accommodated eight men, with a Senior at the head of each and men of different faculties with him. Each table had two freshmen as well, so that the newer student got to know the older. Always there would be a few "impossibles", men whom no table president wanted. These would have their names put into a biscuit tin, and would be "drawn" after prayer, the sole proviso being that no table president should suffer them twice!

The cast of the Trinity College performance of Robert Browning's 'Strafford', 1896.

Trinity College Archives, MM 001755

This mixing up of students at dinner, I consider, was most valuable. It prevented the formation of small knots of men, and in a college with so few residents this was important.

Trinity put on two plays during my time. The first was Browning's "Strafford." Looking back, I recall most vividly the astounding variety of costumes displayed. No two costumes were alike. Our leading tennis player, Leo Miller, looked like a very gentlemanly lion-tamer. George Price - who died, alas, in the Highland Light Infantry in South Africa - as a cavalier, in a rakish hat with a feather, long fair curls hanging down to his shoulders - resembled a very dissolute street-walker, an impression which eight or nine inches of white lace hanging down from the knees of his black satin knickers did not entirely dispel. Most impressive was the headsman, Bert Kiddie, six feet nine inches tall and bearing a ferocious axe.

The other play was "Alcestis" of Euripides, a very ambitious effort, with specially composed music and elaborate scenery, and it was staged in the Melbourne Town Hall.

Remembrances of Walter St. George Sproule (TC 1896), provided to Trinity College in 1961.

Sproule was born in 1878 in Ballarat and educated at Kew High School before entering Trinity College in 1896. He was admitted to the Victorian Bar in 1904 before serving as a Captain in France with the AIF during World War I. In 1926 he was appointed a Crown Prosecutor, before being made a Kings' Council in 1937 - a role he retained until his retirement in July 1949. Sproule was an active member, from 1926, of the Wallaby Club, the Melbourne-based walking group, and was elected President in 1938. He retained his membership until his death in 1968.

Dr Ben Thomas, Rusden Curator, Cultural Collections

Dr Ben Thomas, Rusden Curator, Cultural Collections