What a character!

Long, lost personalities

Over 150 years, a community of staff – often unseen and indeed, unrecorded to history's pages; many consigned to the basement – have kept Trinity College running.

These aren't the credentialed academics or teachers, the administrators or executives; though they are critical to the success of an academic institution.

No, these are the roles that, in decades past, kept the gardens looking their best, attended to the washing of bedsheets and linens, replaced lightbulbs, and both oversaw and had a hand in the physical growth of the campus' built environment as the College rose to meet increasing student demand.

Through two world wars, troughs of economic uncertainty and shifting societal expectations on residential colleges, these staff formed the backbone of the college. And in the process, endeared themselves through personal friendships and memories with generations of students.

These are some of their stories.

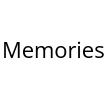

The Gardener and Gate-Porter: 'Old Charlie'

Charles Cameron Eaton, 1857–1913

Born in Glasgow, Scotland, in about 1857, Charles Eaton was 'a capable and zealous officer', 'devoted to the interests of the college', and a familiar face for almost the inaugural four decades' worth of students at Trinity College.

"Old Charlie" – to give him the name by which he was best known to the students – was fondly remembered by several generations of Trinity's earliest students as the College porter and later, in his nearly 40 years' service with Trinity, as the gardener to the Warden.

The College grounds in the late 19th century were far more sparse than they are today, with the Warden's gardens on the southern and eastern sides of the Warden's Lodge being the primary areas that would have come under the responsibility of Eaton.

Eaton was admitted to the Melbourne Hospital in late 1913 for an operation and sadly died from complications, aged 56, leaving behind his wife, Elizabeth (neé Renison) and 10 children.

As the student body lamented in the Fleur de Lys in 1914, 'He will be greatly missed by those who came back to renew their acquaintance with the College, as he never forgot a face.'

The Argus newspaper, announcing his passing, noted:

'When the students of early days visited the college in later life, sometimes bearded and grizzled men, he would instantly recognise them, and have an anecdote of their college days ready for them. The announcement of his death will be read with great regret by old Trinity men in all parts of the world.'

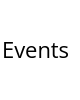

Dorothy Ryall with her husband Lewis Henry Ryall, and their son, William Ryall, c. 1922

Dorothy Ryall with her husband Lewis Henry Ryall, and their son, William Ryall, c. 1922

Dorothy Ryall and husband Lewis Henry Ryall, 1920s

Dorothy Ryall and husband Lewis Henry Ryall, 1920s

On the road - Dorothy Ryall on a family holiday, 1920s

On the road - Dorothy Ryall on a family holiday, 1920s

The Matron: Mrs Ryall

Dorothy Jane Louisa Ryall, 1887–1942

The name ‘Dorothy’ reverberates across multiple generations of Trinity alumni and, now – with the recently completed residential wing in the campus’ north taking the name – current students as well. But the latter may have little familiarity of the woman behind the name.

Born in Malvern, Victoria, in 1887, Dorothy Jane Louisa Newton was the first of two daughters born to Henry Gildea and Isabella Jane Newton. Perhaps due to collapsing business interests with the economic downturn a few years later, Henry and Isabella moved their young family to the regional township of Numukah, north of Shepparton, in the mid-1890s, where Isabella had family connections.

Isabella Newton was an accomplished singer and performed at numerous local concerts and events in and around Numukah in support of worthy causes. Dorothy had evidently inherited these talents and, a talented musician in her own right, was accepted as a student at the Melbourne Conservatorium of Music, University of Melbourne (she was the first student from Numukah to be accepted to the conservatorium).

During her first term, Dorothy made great progress and was selected by the head of the conservatorium, Professor Franklin Peterson, to be one of the student singers at a concert held at the Melbourne Town Hall. Peterson spoke most highly of 'Miss Dorothy' and the possibilities in front of her, and said she had also earned the esteem and love of both students and teachers.

In 1905 the local Numukah community held a benefit concert in order to support her continuing tuition education fees, encouraged by Peterson’s personal assessment of her abilities:

Miss Newton's voice, in my opinion, will repay attention, and if money can be raised to enable her to take advantage of the opportunities the Conservatorium can offer, I am sure Numukah will find the money was well spent.

Family circumstances however were such that Dorothy was unable to complete her studies and, in 1910 she, like her sister Eileen, trained instead as a nurse.

With the outbreak of World War I, Dorothy enlisted as a staff nurse in the Australian Army Nursing Service in April 1915. Ten days later she sailed from Sydney aboard HMAT A55 Kyarra for service with 1 Australian General Hospital in Egypt, where she nursed casualties from the Gallipoli campaign.

In April 1916 she moved with her hospital to Rouen, France, near the Western Front where – over the following 12 months – she nursed in a series of casualty clearing stations, close to the front line. For her outstanding work with these units, she was awarded the Associate (or 2nd Class) Royal Red Cross in April 1917.

Dorothy moved to London at the end of 1918 and was posted to 2 Australian Auxiliary Hospital at Southall throughout December before returning to Australia aboard HMAT Aeneas in February 1919, where she was placed in charge of the nursing staff. She was discharged from the army in April that year.

Dorothy’s sister, Eileen, also served with the Australian Army Nursing Service, in India. When Eileen returned to Melbourne she was posted to 11th Australian General Hospital at Caulfield from April 1919 to April 1920. During a visit to her there, Dorothy met and began a relationship with Warrant Officer Lewis Henry Ryall, formerly a law student at the University of Melbourne prior to his enlistment, who had been severely wounded at Villers-Bretonneux. The couple married in 1921 and moved to Queensland for Lewis’ health. Their only child, William Henry 'Bill' was born in 1922.

Lewis Ryall died in 1927 from complications relating to his war service, and Dorothy and her son returned to Melbourne where, replacing Miss Burke, she took up the position as matron at Trinity College, Melbourne University, in late 1929.

As the students noted with appreciation in the Fleur de Lys magazine later that year:

Mrs Ryall at once settled down to her new life and we must congratulate her on the capable manner in which she is looking after us. We thank her for the care with which she keeps brightening flowers in the common room and hope that her stay with us will be a long and happy one.

Like many army nurse veterans in the interwar period who took up posts as matrons across schools, colleges and hostels in Victoria, Dorothy’s own prior military service suggests she was a capable and efficient matron, and she was respected amongst her nursing peers as one 'who holds the coveted Royal Red Cross for her war work'.

This was clearly combined with a maternal and empathetic outlook to the young men under her charge, and the College community, which itself had gone through great loss during the war.

Small vignettes of this appreciative relationship between students and matron are littered throughout the Fleur de Lys magazines. 'We must express our sincere gratitude to Mrs Ryall for many courtesies which she has rendered to us', the students wrote in 1931.

Tastefully arranged flowers are never absent from the War Memorial [in the Common Room], while, on open nights, our rather dismal Common Room is made to appear quite inviting by her efforts. Particularly do we appreciate her valuable assistance to us in arranging our last Valedictory Dinner.

Trinity faced renewed difficulties with the outbreak of World War II, both in the loss of student numbers but equally the difficulty in securing suitable staffing.

There has, since the war began, been very great difficulty in obtaining the Domestic Staff. Mrs Ryall is to be congratulated on the way she has kept that side of the College running smoothly. She has had almost unsurmountable difficulties to overcome, but regardless of this, the usual good quality of College domestic service has been maintained. Thanks are also due to those members of the staff who have remained with us through thick and thin.

The student body was 'deeply shocked' when, on 9 March 1942, aged 54, Dorothy Ryall died at a private hospital in Melbourne.

A few years prior to her death, in 1937, the College had built a new domestic staff quarters in the north-east corner of the campus, against the boundary with the University of Melbourne. It soon became known to students of the late 1930s as ‘Dorothy’, owing to her supervision of the domestic staff that resided there. The building would remain the quarters of domestic staff at Trinity up until 1980, at which point it was converted to accommodate 13 residential students.

The staff quarters were demolished in mid-2018 to make way for the new residential wing – the Dorothy Jane Ryall building (or 'Dorothy' for short) – named in continuing recognition of matron Dorothy and all those often nameless staff that have served the College over 150 years.

The Overseer: Syd

Sydney Arthur Edmund Wynne, 1902–1971

On 3 March 1920, the minute book of the College Council recorded a brief note, describing the role of Overseer, noting that, 'it was resolved that Mr S. Wynne be appointed a permanent employee of the College at £5 per week to keep the property of the council in thorough order, and be responsible for all repairs ... that be found necessary.'

All repairs, that is, 'other than paper-hanging and sanitary plumbing'!

Born in Camperdown on the edge of Victoria’s Western District, Syd Wynne was 18 years old at the time, though already well acquainted with Trinity College.

His father, Shropshire-born Sydney Snr, had also been associated with Trinity in a similar role, and so, as a young boy, Syd 'knew the College in the halcyon days before the First World War.'

It seems probable that one of Syd's earliest tasks was overseeing the construction of the temporary residential building on the north side of Clarke building, known as the Wooden Wing. Four decades later, he would still be under the College employ as he partook in the Wing's demolition.

Together, the duo of the Syd Wynnes – senior and junior – are credited with the construction of the recently lost sandstone building, dubbed 'Vatican', whose stonework now forms the eastern wall of the decking that extends southwards from the new Junior Common Room in the Dorothy Jane Ryall building.

The Warden’s former tennis pavilion, quaintly known as the Summer House, was another building of the mid 1920s credited to the Wynnes which – like the Vatican – was rumoured to have been made with 'stone acquired somehow or other from Newman College and St Paul’s Cathedral.'

Following his father's death in July 1930, Wynne Jnr would go on to oversee the construction of the Deanery along Tin Alley in 1936, and no doubt supervised the completion of the squash court two years later, adamantly marking the extent of Trinity’s far south-east boundary corner in the face of attempts by the University of Melbourne to widen Tin Alley.

Where paths were installed, buildings renovated and extended, and all manner of other tasks relating to the proper upkeep of the campus, Wynne was present. Even the student body, in 1944, recognised that his 'services are invaluable to the college'.

In 1949, when the old timber front gates and fences were replaced with new (and still remaining) gates of stone, the work was carried out under 'the eagle of eye of S. Wynne, Supervising Architect'. Indeed, at the same time a new gate was installed directly opposite the entrance to the Chapel leading on to Royal Parade.

This, the students surmised, was 'so that people getting married can go straight in and out.'

The Overseer role was on the cusp of expanding as post-war demands placed pressure on the College. When Miss Rushton, the Matron who had replaced Dorothy Ryall seven years earlier, resigned, Wynne took on the responsibility of overseeing the house and catering, in addition to his property maintenance duties.

All-male staff were employed in the Hall and other buildings, and the students bemoaned the fact that,

‘we now have to make our own beds and clean out our own bedrooms. No one particularly approves of this latter change, but most seem to prefer it to the further increase in fees which would otherwise have taken place.’

Though the students recognised that the financial necessity of reducing domestic staff had placed an added burden on Wynne, 'and we are very grateful to him for all that he has done'.

Robin Sharwood, writing in 1970 at the point of Wynne's retirement from Trinity after an incredible half century of employment, recounted an amusing anecdote. Wynne had known four Wardens, and formally worked under three of them. As the years passed, and his role expanded, his authority of certain areas of College life 'grew to awesome proportions'.

'Not for nothing was the story told of the innocent freshman who enquired of this commanding if casually attired figure where he could find the Warden; "I’m the bloody Warden", said Mr Wynne, "what do you want?"

Syd Wynne retired at the end of April 1970. Despite his imposing familiarity with the College, he was nonetheless a modest and retiring figure, reluctant to be thanked by a public occasion. He was brought into a meeting of the College Council, his impressive tenure noted, and then, 'after half a century of unbroken service, Mr S. Wynne slipped quietly away, without any ceremony, into what we must presumably describe as his retirement.'

Sadly retirement did not last long. Almost a year to the date, Syd Wynne passed away on 22 April 1971. He is remembered today at Trinity through a bronze medallion by noted sculptor Peter Corlett at the entrance of Clarke's building, and the enduring legacy of the Syd Wynne scholarship, established upon his retirement.

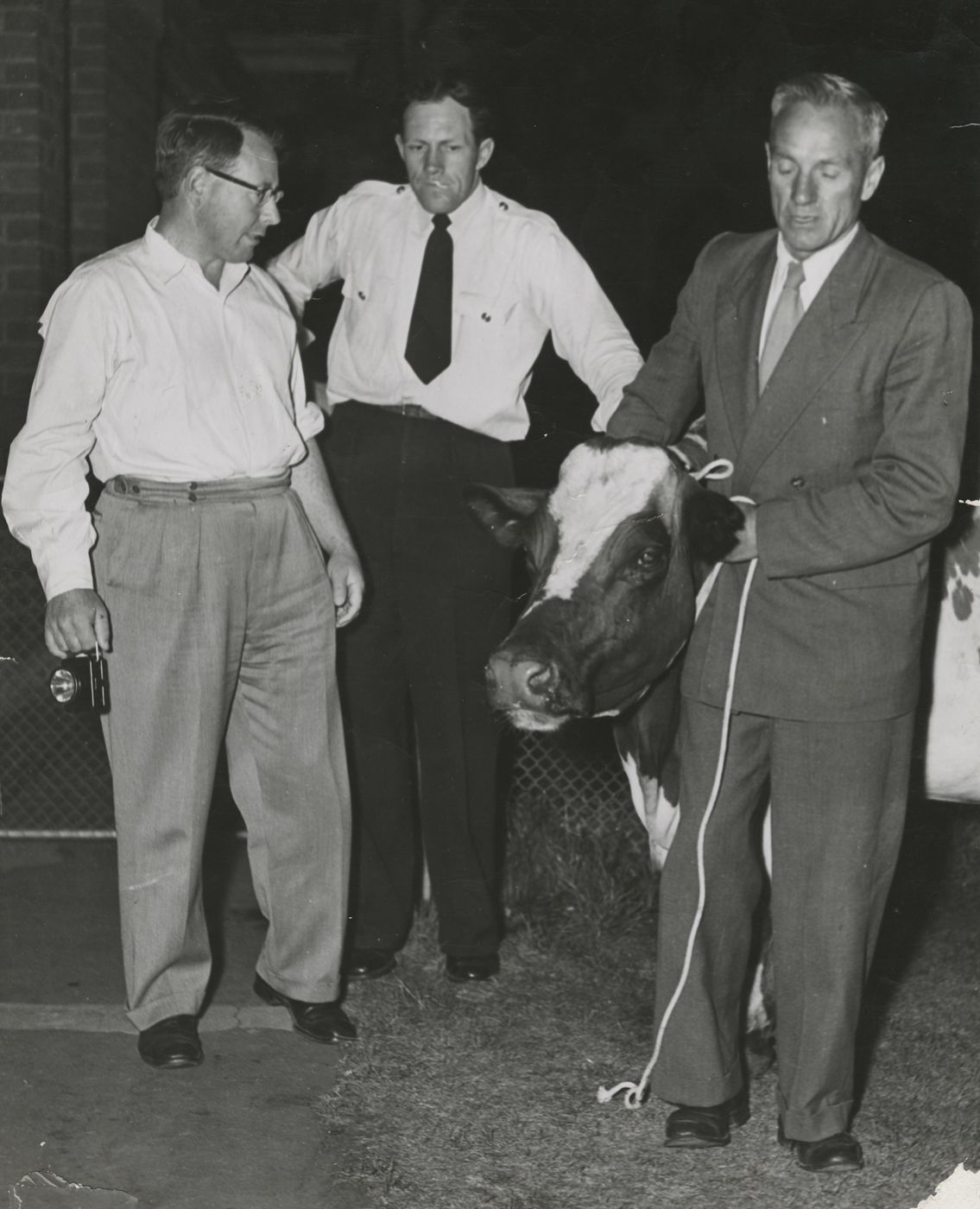

Syd Wynne, with Warden Ron Cowan and a police officer after retrieving 'Daisy', a college cow that escaped up Royal Parade, March 1956

Syd Wynne, with Warden Ron Cowan and a police officer after retrieving 'Daisy', a college cow that escaped up Royal Parade, March 1956

Syd Wynne inspecting timber out the front of Leeper Building during the extension of the Dining Hall, 1954-55.

Syd Wynne inspecting timber out the front of Leeper Building during the extension of the Dining Hall, 1954-55.

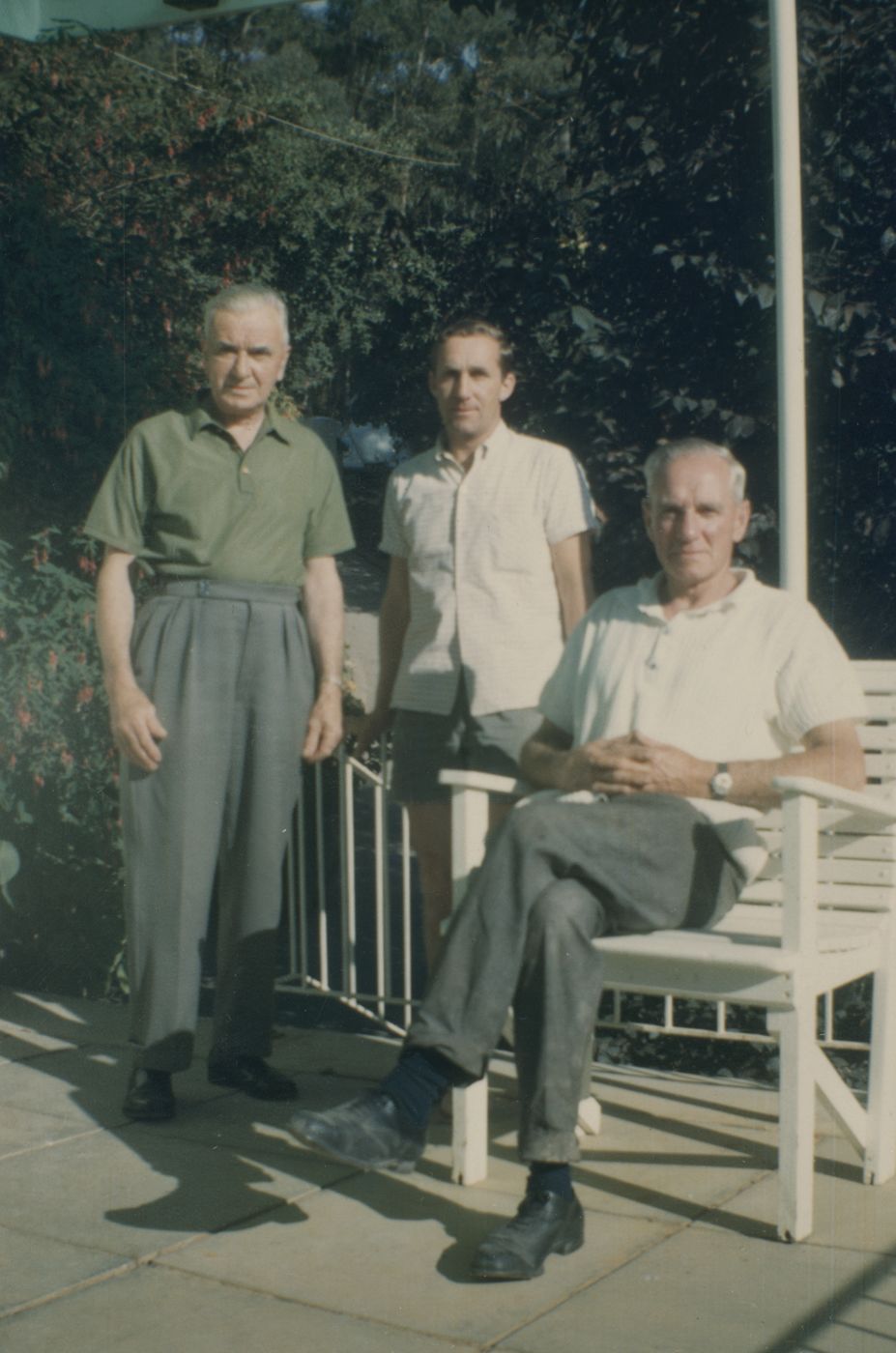

Syd Wynne (seated) with friends, c. 1960s

Syd Wynne (seated) with friends, c. 1960s

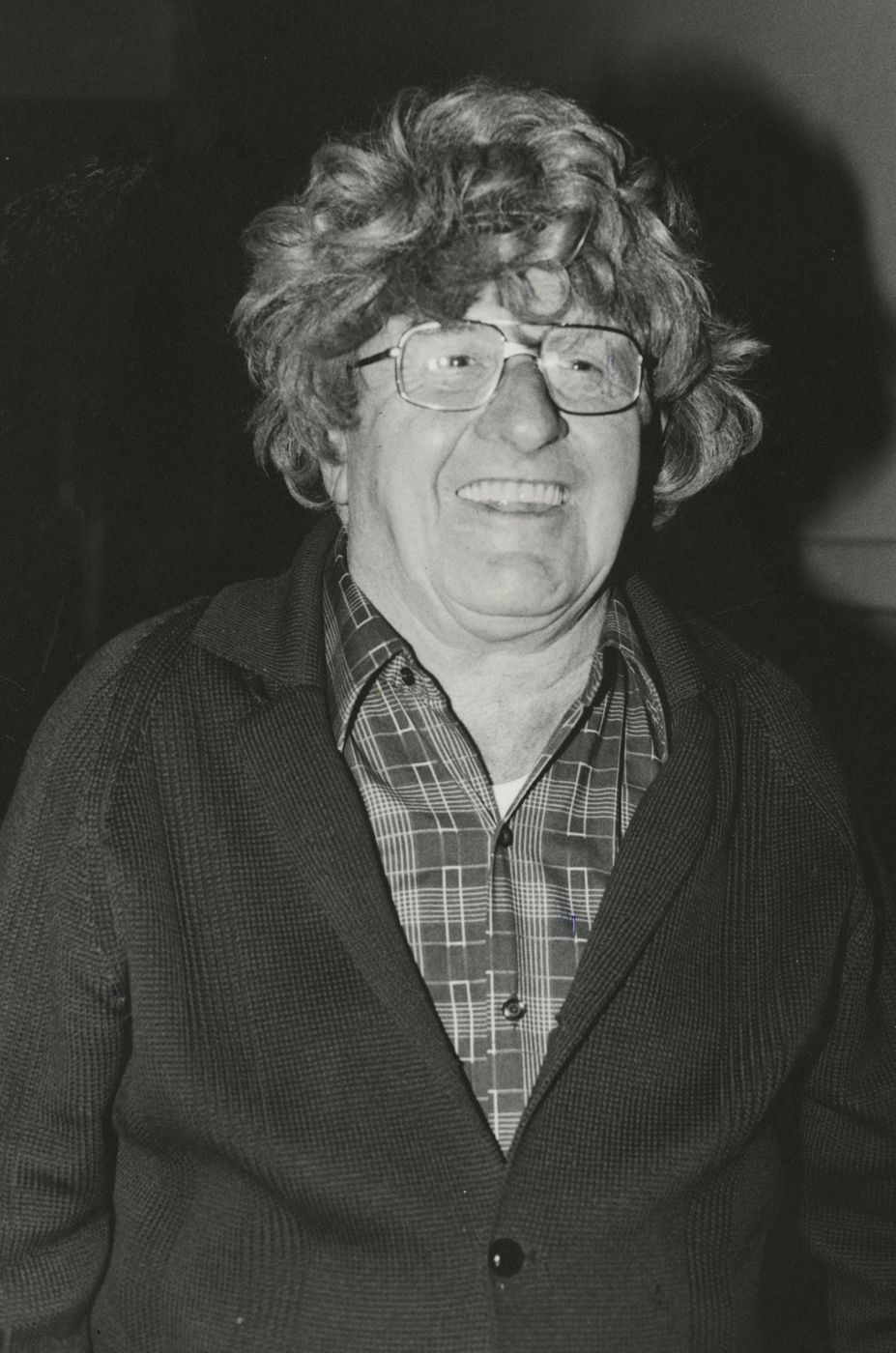

Arthur Hills modelling a wig for the camera

Arthur Hills modelling a wig for the camera

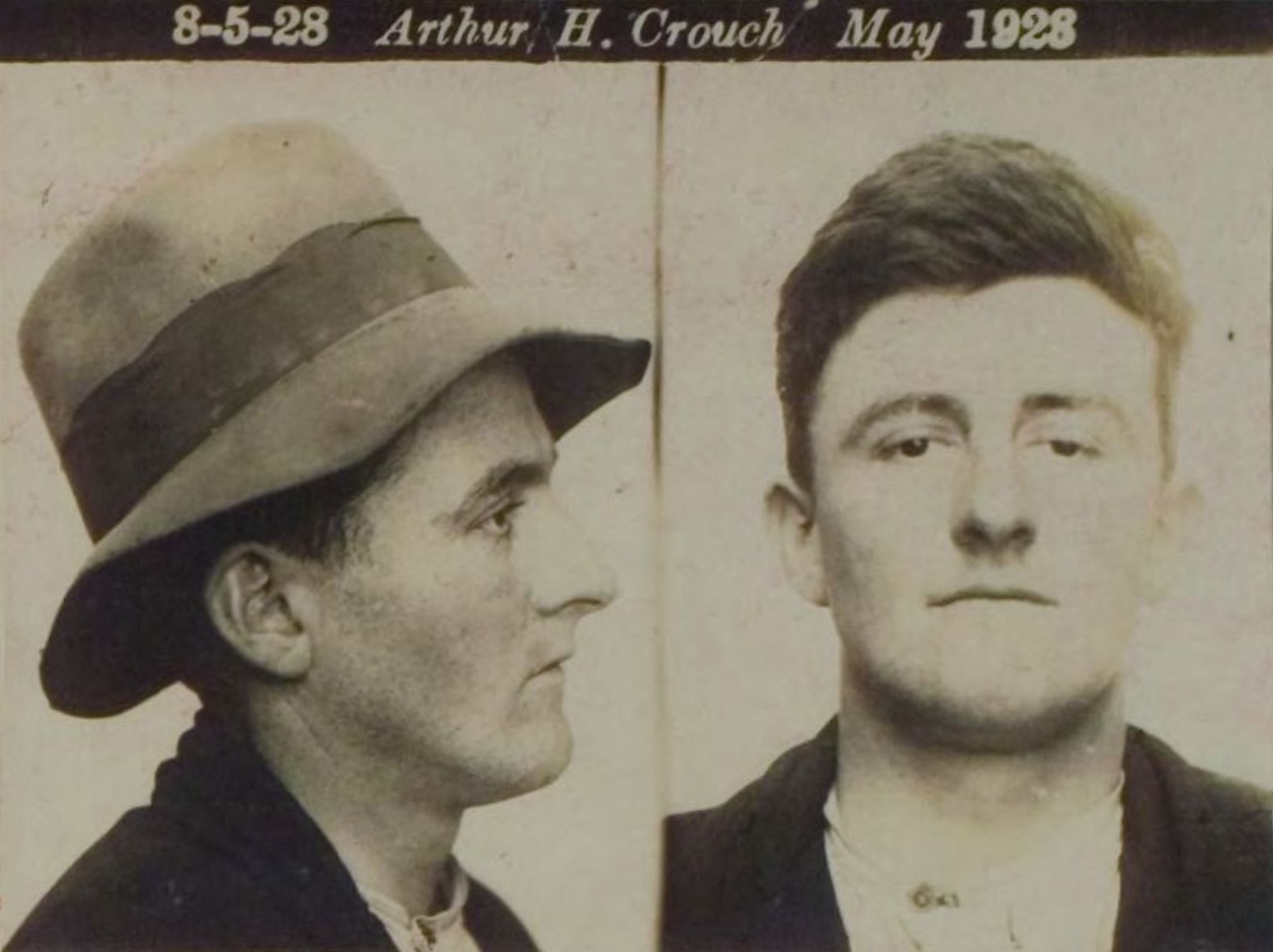

Arthur H. Crouch, Central Register for Male Prisoners, Public Records Office of Victoria, VPRS 515/P0, 39647

Arthur H. Crouch, Central Register for Male Prisoners, Public Records Office of Victoria, VPRS 515/P0, 39647

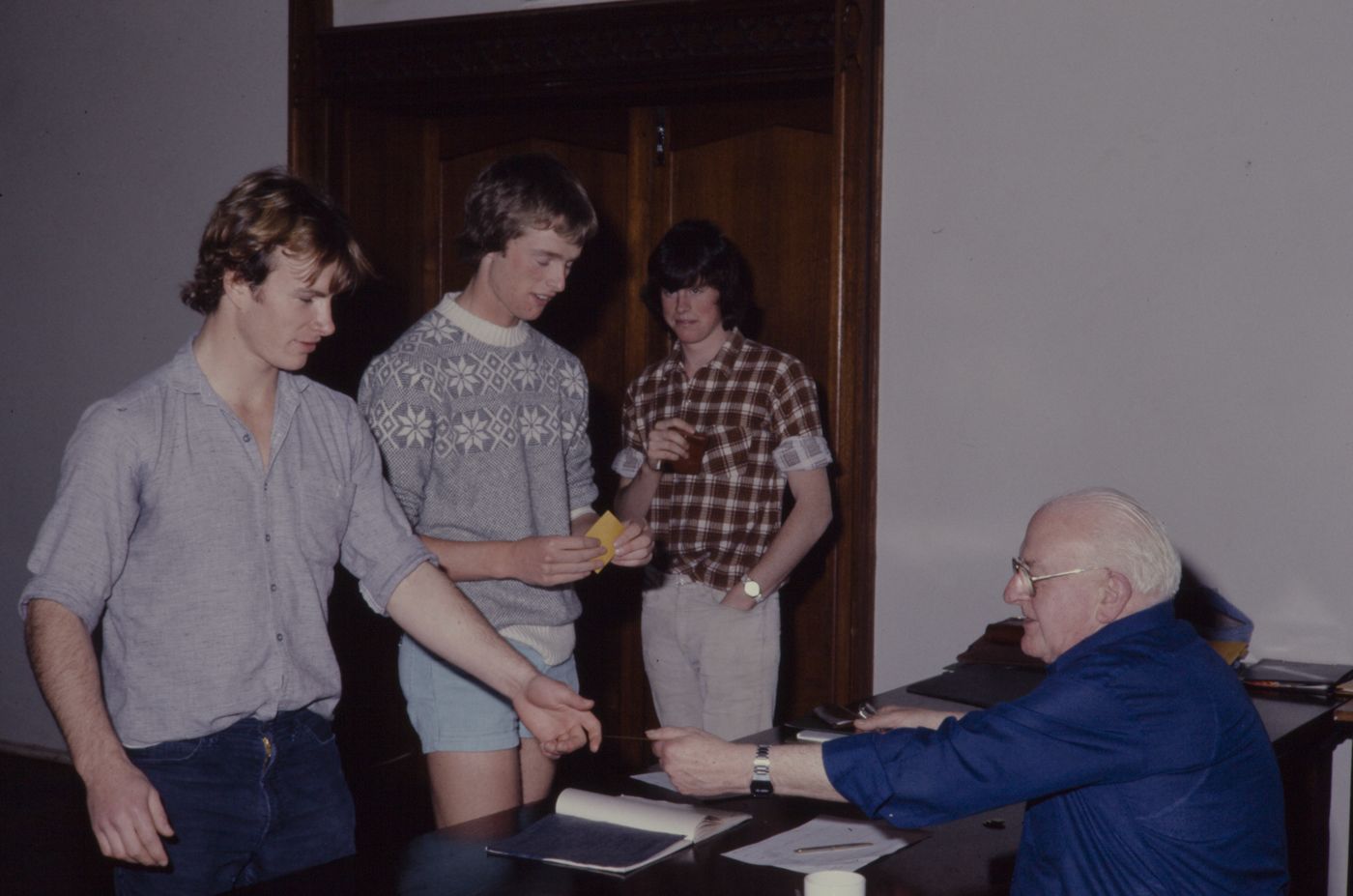

Arthur Hills with students in the Dining Hall, 1980s

Arthur Hills with students in the Dining Hall, 1980s

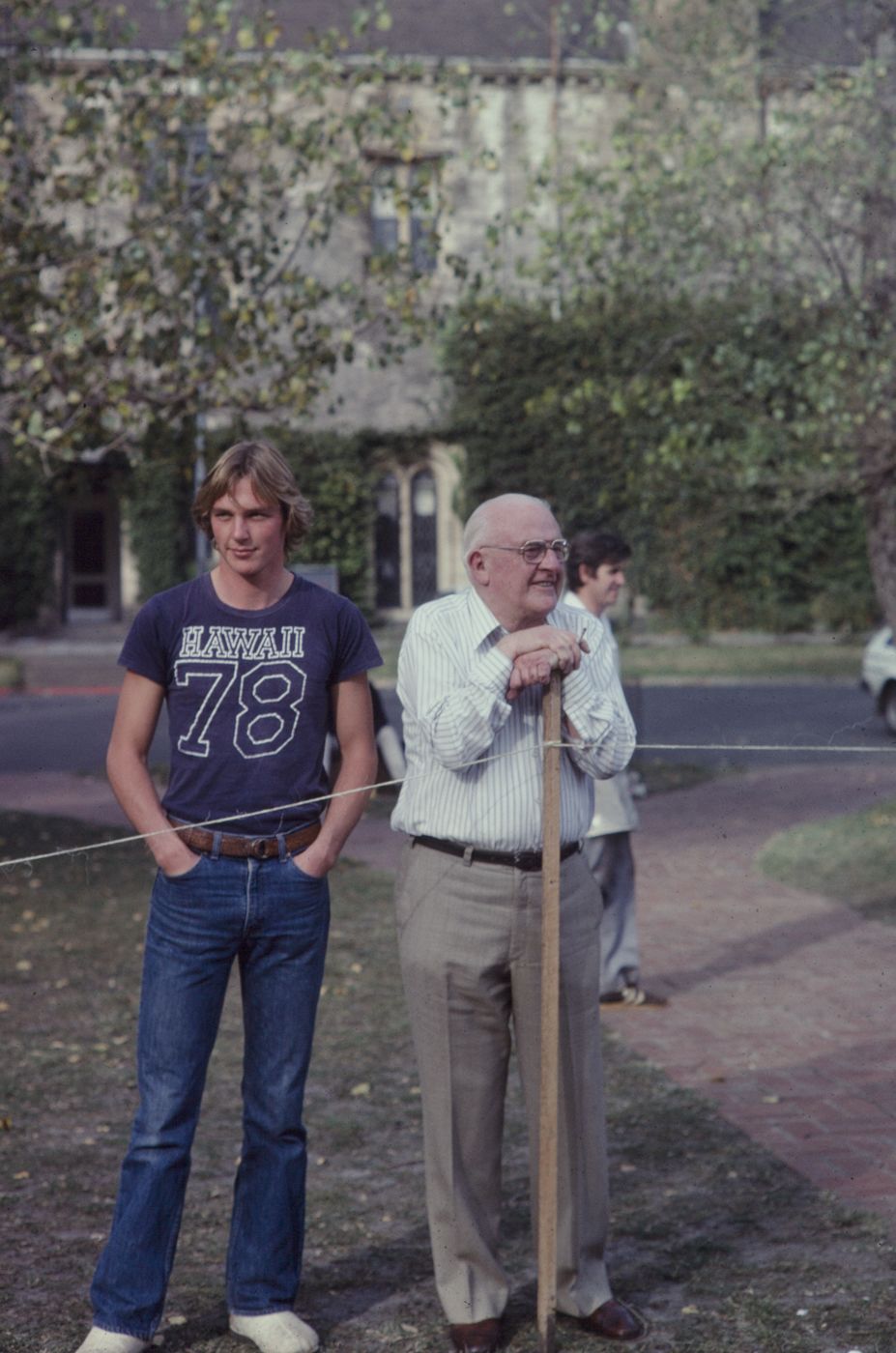

Arthur Hills surveying the Bulpadock with Bill Peden (TC 1979)

Arthur Hills surveying the Bulpadock with Bill Peden (TC 1979)

The College Porter: 'Artie'

Arthur Hills, 1911–1986

'Five months ago this Chapel was crowded to overflowing as the present College generation gathered to honour perhaps the greatest College benefactor, Arthur Hills or ‘Artie’, the College Porter.’

Trinity’s fifth Warden, Evan Burge (1974–1997), recalled that when Arthur Hills was engaged as Porter in 1973, the College Council had been told that the profits from running the small shop situated in Bishops’ building, just outside the entrance to the Hall, would be sufficient to pay his salary.

‘What happened in fact was that the shop ran at an ever-increasing loss until it had to be closed. Arthur couldn’t sell things – he preferred to give them away.’

All the same, both the Warden and the College's Bursar John Wilson were staunchly behind Arthur's continued employment, finding him 'invaluable in maintenance and student liaison'.

Even almost half a century after he commenced at Trinity, many aspects of Arthur's life remain a mystery. Despite his friendliness, it was remembered after his death, 'he was essentially a very private person. Even his name and birthday were unknown'.

Medical records suggested he was born in 1920; the Department of Social Security, who claimed to have once sighted a birth certificate, had it recorded as 1911. They were closer to the mark.

As it turned out, Arthur Harry Ernest Crouch was born on 7 July 1911 in New Zealand to Australian parents Henry and Lily Louisa (neé Johnston). He was the first of two children, with his sister born in 1915. At some point, the family moved back to Australia. Lily would marry a second time to Henry Hills and, in time, young Arthur would adopt his stepfather's surname.

Arthur's life before Trinity is pieced together, even now, largely by anecdote and recollection. That said, archival records have shed invaluable light in some previously dark corners.

In 1928, in what would be the first of several such occurrences, Arthur – then 17 and working as a labourer – appeared before the courts on a charge of 'insufficient means'. Similar charges of larceny, unlawful possession, and vagrancy would be repeated over the following five years.

These were the years of the Great Depression, following the Wall Street Crash in 1929.

In Australia, at its peak, unemployment edged towards 30% in 1932. That year, Arthur would appear before the Carlton Court on a charge of falsely claiming sustenance payments. Police Magistrate Edward Tibb noted that Arthur had 'apparently taken no warning from the other conviction, and should be put in a place where you will not need sustenance of the type you have been drawing.' He was sentenced to 12 months jail, the bulk of it spent at Pentridge prison. Shorter sentences had already been endured, and others would subsequently follow, as the impacts of the Depression lingered on.

Rumour had it that Arthur was apparently once married to a dancer in the ballet at the Tivoli, but the relationship only lasted nine months. Arthur himself had spoken of his time working at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, and the College's fifth Warden Evan Burge had 'a strong feel he had nursed psychiatric patients at some stage'.

Judgements are easily made at a distance, but Arthur's colourful past undoubtedly shaped his employment at Trinity. As College Porter, his interactions with the residential students were frequent and personal, leaving a deep impression on those who knew him.

Little surprise that his tendency was to give things away from the College shop; he had experienced first-hand what it was like not to have anything. He never married, nor did he have any children.

Trinity became his community and his family.

Arthur would sort the mail, delivering it to the students' mail boxes, keeping a watchful eye for that 'special letter' that was eagerly awaited. Stubborn coins that had jammed the washing machines or phone box (when there was still a telephone box in the Clarke cloisters) would be dealt with; an electrician or plumber called out late at night or on weekends if a building was suddenly plunged into darkness, or an unexpected river found washing down a corridor.

The Porter would ring the bell to announce formal Hall and stand at the entrance to greet students as they processed in, listening – probably with a wry smile – to the unlikely excuses that dress standards had slipped on account of their gowns still being at the dry cleaners.

Arthur seemed to know everything about everybody. And he never forgot anyone.

'The Redoubtable Artie', one female alumna of the 1970s described him, alongside 'his sidekick the gardener Frank Henagan, long before Frank became iconic'. Or as another alumni from that period recalls fondly,

"Well … Arthur was a combination of your grandfather, father and best mate. He seemed to know exactly what you had been up to, and often you would have to check with him if you had forgotten what you had done. The twinkle in his eye always put you at ease, irrespective of whether you were a fresher or a seasoned campaigner."

When the annual Portsea-to-Parkville Trike Race was held in 1977, a committee was formed to develop Trinity’s prototype model to compete. It is perhaps telling that in selecting a suitable name, the three-wheel assemblage was christened 'Arthur Hills' (with beer, by the Warden, no less!). Battered and bruised, the home-made contraption reached the University campus in 14th place that year, but was rejuvenated to compete once again the following year.

Arthur retired in 1983 but continued to perform some duties. His sudden death in 1986 shocked the College community. He had been found unconscious by his friend and colleague, the College gardener Frank Henagan, and, despite the best efforts of the paramedics, could not be revived.

Arthur's passing left an immeasurable hole for a generation of students and alumni. Warden Evan Burge would encapsulate the sentiment, noting that in 'the truest sense, Trinity College was his family for the past 13 ½ years, and we are his grieving and grateful family now'.

Like Syd Wynne before him, Arthur Hills was recognised by the College with a scholarship being established the following year, in 1987. It continues to help residential students experience Trinity to the fullest extent; in every bit in keeping with what 'Artie' would have wanted.

Dr Ben Thomas, Rusden Curator, Cultural Collections

curator@trinity.unimelb.edu.au